Visualizing the Range of Glaciers

This page served as a landing spot for sharing bits of my undergraduate environmental science honors thesis and related printmaking work. The North Cascades in Washington, the place I know as home, hold many glaciers that have complex ties to both ecological and human communities. Climate change is rewriting the state of these glaciers and the relationships that they can sustain. Although these connections are usually described by science, art is an expansive form of communicating a shifting landscape and its inhabitants. My project strove to explore a remarkable place in flux with various ways of knowing - scientific, personal, artistic, anecdotal. Enjoy these snippets, or download my entire thesis “Visualizing the Range of Glaciers: Science, Art and Narrative if you care to.

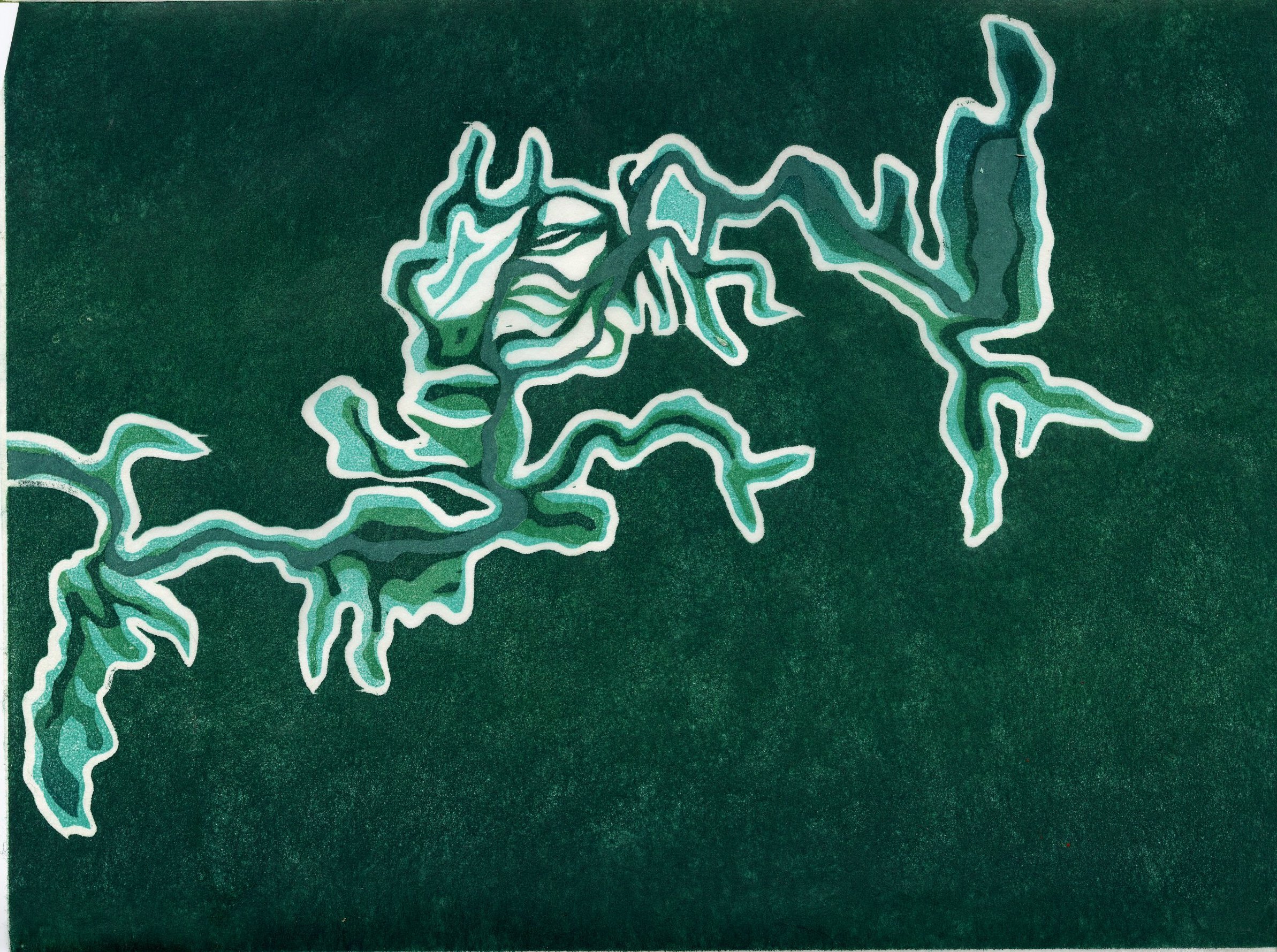

Sholes Imprints

Facing Mt Baker and the upper part of the Sholes Glacier (terminus below to the right). Can you see the forms of creatures emerging with the bare ice?

The Sholes Glacier flows down the north east side of Kulshan/Mt. Baker in Washington State. It feeds the North Fork of the Nooksack River, the short icy artery that connects Bellingham Bay to Kulshan, the 10,781 foot tall volcano. The Nooksack tribe calls this land home. So do many furry, scaly and feathered brothers and sisters.

Spend any time near the mountain and the lives of animals will quickly chirp, swoop, slap and wriggle their way into your awareness. This summer I spent a night on the Nooksack River, and I could feel the silver splash of salmon and the gaze of an eagle all evening. Later, we hiked Ptarmigan Ridge and counted nearly 50 mountain goats. The gray flash and squeak of pika is a frequent companion alongside the trail. These animals are emblems of the North Cascades. They are also endangered, each impacted by retreating glaciers and changing climate in different ways. With these imprints inspired by the Sholes Glacier, I show the beauty of their symbolic bodies and experiment with how we feel in their absence.

Back in July, I had a conversation with Jezra Beaulieu, who works as a water resources specialist for the Nooksack tribe. We discussed the research that she and Oliver Grah do, the connections between glaciers and salmon habitat, and how the Nooksack tribe is planning for climate change. In the portion of our conversation where I asked (as I always do) what forms of communication she found particularly effective at imparting data related to ongoing environmental change and adaptation, she mentioned the Nooksack Vulnerability Assessment.

“The climate of the Nooksack River watershed is changing, and is projected to continue to change throughout the 21st century. In addition to rising temperatures and exaggerated patterns of seasonal precipitation, the watershed is likely to experience greater wildfire risk, more severe winter flooding, rising sea levels, and increasing ocean acidification. These changes will have profound impacts on the watershed’s plants, animals, and ecosystems, including changes in species distributions, abundances, and productivity; shifts in the timing of life cycle events such as flowering, breeding, and migration; and changes in the distribution and composition of ecological communities. Understanding which species and habitats are expected to be vulnerable to climate change, and why, is a critical first step toward identifying strategies and actions for maintaining priority species and habitats in the face of change.”

Morgan, H., and M. Krosby. 2017. Nooksack Indian Tribe Natural Resources Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. Climate Impacts Group, University of Washington.

The Nooksack Vulnerability Assessment can be found here. It assesses how climate change will impact 18 important species and 6 habitats within the Nooksack watershed. There are different sensitivity factors impacting the species. The information is presented in tables grouping vulnerable species under different RCP scenarios. Most species end up in the “Extremely vulnerable” category by 2050 and 2080. This is gloomy information, presented in a straightforward scientific manner.

These analysis of species vulnerability inspired me to start printmaking. I expanded upon the simple silhouette imagery used in the report and carved intricate animals from wood, then embossed those forms in thick paper, or printed them in ghostly shades of grey. I thought about fragility, transience and resilience in addition to vulnerability. I printed these animals by themselves, or under the strong and enduring outline of Mt. Baker. In the present, these animals characterize this place. Their bodies are linked to water bodies. They populate the Nooksack watershed and fill ecosystem niches. In the next 30 or 60 years, will they still be here? How will they adapt? What would this place be without them? These are the questions driving this work.

This ongoing experiment is one example of how I am creating data-inspired visuals, bridging art and science with the help of photographs, experiences and conversations with researchers and watershed stakeholders.

Bodies of Water

The first print here is an embossment of the Company Glacier path, carved into birch plywood this June, in Stehekin. The process of embossing entails pressing damp paper into a block to take on its sculptural qualities. Without color, the this print traces a water body of which we, flowers, lightbulbs and orchards are the downstream organs. A three minute cascade of sounds follows the image. Let your eye and ear simultaneously trace the trees and wires bleeding from the current. Imagine this place as a sponge, where water is the common medium for all - orchardist, phytoplankton, marmot, mountaineer, tardigrade. Meltwater springs, sings and sloshes from the glacier to the lake, enlivening everything along its path.

Notes from Cascade Pass

On a recent trip to Cascade Pass and other places in the North Cascades where I had not been before, I kept a small spiral bound notebook with a black cover in my pocket at nearly all times. As ideas welled from my path, I wrote them down. I also noted sightings of species, surroundings and people. This was an unplanned practice of close observation. Writing down what jumped out at me helped me sort through what might be important, interesting or significant. In some cases, I became absorbed by minute details, like the physics of butterfly flight. In other moments, the history of the landscape took over and I jotted down the gestures of glaciation sweeping the valleys. My attention adapts to the rhythm of the land. This type of attunement is not easy for me to come by. A long span of time alone in the mountains is one place that I find it. Writing down the path of my thoughts may help preserve it.

At Cascade Pass, there was an abundance of terrain, life and visitation to take in. Writing down short notes was a way to document what was happening, a loose frame of the stories that converged at Cascade Pass that noon hour. Here, I copy my notes from an hour at Cascade Pass to share the experience of being in that new place, and to help me think about the broad and specific stories that are played out in this alpine area day after month after year. As I was taking these notes, I felt a strong sense of companionship with Terry Tempest Williams in her prairie dog days. In spring of 2004, she joined the Utah prairie dog scientist John Hoogland for fourteen days, and detailed her observations and reflections for 110 remarkable pages in the book Finding Beauty in a Broken World. I don’t think anything has taught me as much about observation in the natural world as the writings of Terry. I’ve never met her, but I could feel her presence as I took notes, being mindful of precise time and place, but also open to my own sensations and the words rising in my mind. I recognized Terry there when I was attuning myself to the character of the marmot, but cutting into my attention was the choking motor of a chainsaw doing trail work. It felt like a twin moment to one of those in Terry’s tower above the prairie dog city.

“The degree of our awareness is the degree of our aliveness.”

Terry Tempest Williams

12:10 I’m on the last couple of switchbacks rising to Cascade Pass. A set of loping tracks head straight up a snowfield. They’re about two inches wide and four inches long, with five toes and apparent claws. On one side, a line in the snow is carved by the tracks sweeping outward. Maybe the prints are too small to be a wolverine…

12:13 Sahale Arm trail is closed for trail work. A line of four people in drab national park service uniforms, bright orange helmets and large packs are walking towards a switchback on the closed trail.

12:15 I arrive at the saddle and settle into a nook in the talus. To my north is Sahale mountain. To the south is an impressive chain of peaks: Johannesburg Mountain, Cascade Peak, the Triplets, Mix-up Peak… and they continue.

12:17 Notice snow sliding down the cracked snow patch below Johannesburg mountain col: henceforth known as J col G, Johannesburg Col Glacier, although it is probably just a snowfield and not permanent ice.

12:30 Group of three mountain goats walk up the west side of the pass. They march up a user trail to a patch of snow already scattered with hoof and boot prints. Mom beds first, then the baby. The subadult wanders a little further to the shadow of a tree upon the snow. They get up and move again after 2 minutes of rest.

12:32 J col G cracks and rumbles. The body splits off 2 big snowballs. They roll down a steep slope of snow and break apart in midair, over the waterfalls.

12:35 J col G rumbles again. I wish I had binoculars. There is a heap of bluish crumble below the steep north face of Johannesburg mountain.

12:36 Goats rebed, on a southern aspect of the snowfield. It’s a warm, dry day. To the West are a few clouds. Their shade is welcome.

I notice that below Cascade Peak and the Triplets is a snowfield with a bergschrund and cracks. There is not ice visible. The snowfield is shaped like a ghost with long arms and pieces of its belly missing.

12:40 A rumbling rockslide on west side of Mix-up peak. Triggered by waterfall? Spray and stone fall off the cliff. All of these peaks are hewn from forbidding dark stone, broken only by snow ribbons clinging to the gullies.

Notice a cornice on the east rib of Triplets

N snowfield of Mix up peak has a little schrund

12:43 Man approaches resting goats. They run off. Man shuffles after them.

Noticing all of the vegetation around me: thick pink heather, hundreds of young spruce trees wafting in the breeze. Rodents shriek.

12:47 Distinct call of pika

12:50 Intricate meadowlark-like bird song on west side of pass

12:53 Hiking couple confirms J col G has been crackling for the last half hour. More chunks break off. The waterfall appears to burst for a moment. J col G looks like it could slide off the slope at the slightest echo of its own fracturing.

Looking north west, the base of a broad snowy peak is visible. The top is clouded.

To the south east, a line below the peaks appears. It heads below Mix-up peak, towards what my map says is Cache Col. Looks like footwork. Could it be the Ptarmigan traverse?

12:58 3 day-hiker kids and parents walk down the trail. They reach a bend in the trail and point down to something. I hear water flowing beneath the snowfield I sit near.

13:00 I walk down the trail to where the kids were pointing. I see a parking lot. Dozen cars.

13:05 Three older men pass by, on their way back to the parking lot. They hike in the Cascades a lot. I ask what changes they’ve seen. They haven’t seen any significant changes here but they exclaim at the glacial change they’ve witnessed on Mt. Baker.

13:06 Cross back over the official top of the pass. Unexpectedly, there is a full semicircle of boulders and flagstone paving create a very structured resting place there. A couple sits on the rocks. “Wow, a fully furnished lookout” I say in passing. They nod and laugh and look east.

13:09 Walking south on a user trail to the start of the Ptarmigan traverse. Goat fur adorns the limbs of spruces like wisps of a colder season. I notice that the alpine huckleberry plants don’t have berries yet, but squishy pink bells midway between fruit and flower. Sense of profound peace in the sun and breeze. Look East to McGregor – it has hardly any snow. Librarians Ridge is bare and tan. From here I can only see a few swoops of white on the northwest ridge. There has been a lot of change within the past month. New plants unfurl where days ago there was snow. I find a perch. The range of observation topics is remarkably wide.

13:14 Grouse woofs in the spruce. Goat scat fills the ditch of the climbers trail.

13:17 A motor roars across the cirque. The National Park Service crew working on Sahale Arm trail has power tools and hammers.

13:22 A large, lone hoary marmot lounges on a boulder in the midst of the climbers trail. The sun is hot. I crouch beneath a sapling before I reach the marmot, hoping to give both him and I some peace. He notes my awkward rustling and cheeps at me. From the shade beneath the spruce tree I can see Sahale Peak, a snowy pyramid. On the other side is Sahale Glacier, I saw it when I hiked past Horshoe Basin. Another impressive something peeks beyond the arm of Sahale mountain… Buckner Mountain? I feel hungry again.

13:27 Marmot tires of my watchful eye, sneezes, and enters a cave in the talus.

More chainsaw.

Pelton Basin below me is tranquil, half snowed and half soggy meadow. I have a strong urge to go swimming. Since the trail to Doubtful Lake is closed I will have to wait until I go down from the pass. I have already moved 11 miles today, and there are 11 miles back to my camp. I feel gratitude for having the ability to travel quickly, and see much. I think about adventure scientists, people who can utilize unique skillsets to take data in remote places.

13:31 Birdsong throws me out of my quiet thoughts. Is it time to get down?

13:36 A bald eagle floats over the pass. Soft song of wind in the spruces is torn by the chainsaw, again.

13:46 I leave the pass.

“We have forgotten the virtue of sitting, watching, observing. Nothing much happens. This is the way of nature. We breathe together. Simply this. For long periods of time, the meadow is still. We watch. We wait. We wonder. Our eyes find a resting place. And then, the slightest of breezes moves the grass. It can be heard as a whispered prayer.”

Terry Tempest Williams.