Visualizing the Range of Glaciers

This page served as a landing spot for sharing bits of my undergraduate environmental science honors thesis and related printmaking work. The North Cascades in Washington, the place I know as home, hold many glaciers that have complex ties to both ecological and human communities. Climate change is rewriting the state of these glaciers and the relationships that they can sustain. Although these connections are usually described by science, art is an expansive form of communicating a shifting landscape and its inhabitants. My project strove to explore a remarkable place in flux with various ways of knowing - scientific, personal, artistic, anecdotal. Enjoy these snippets, or download my entire thesis “Visualizing the Range of Glaciers: Science, Art and Narrative if you care to.

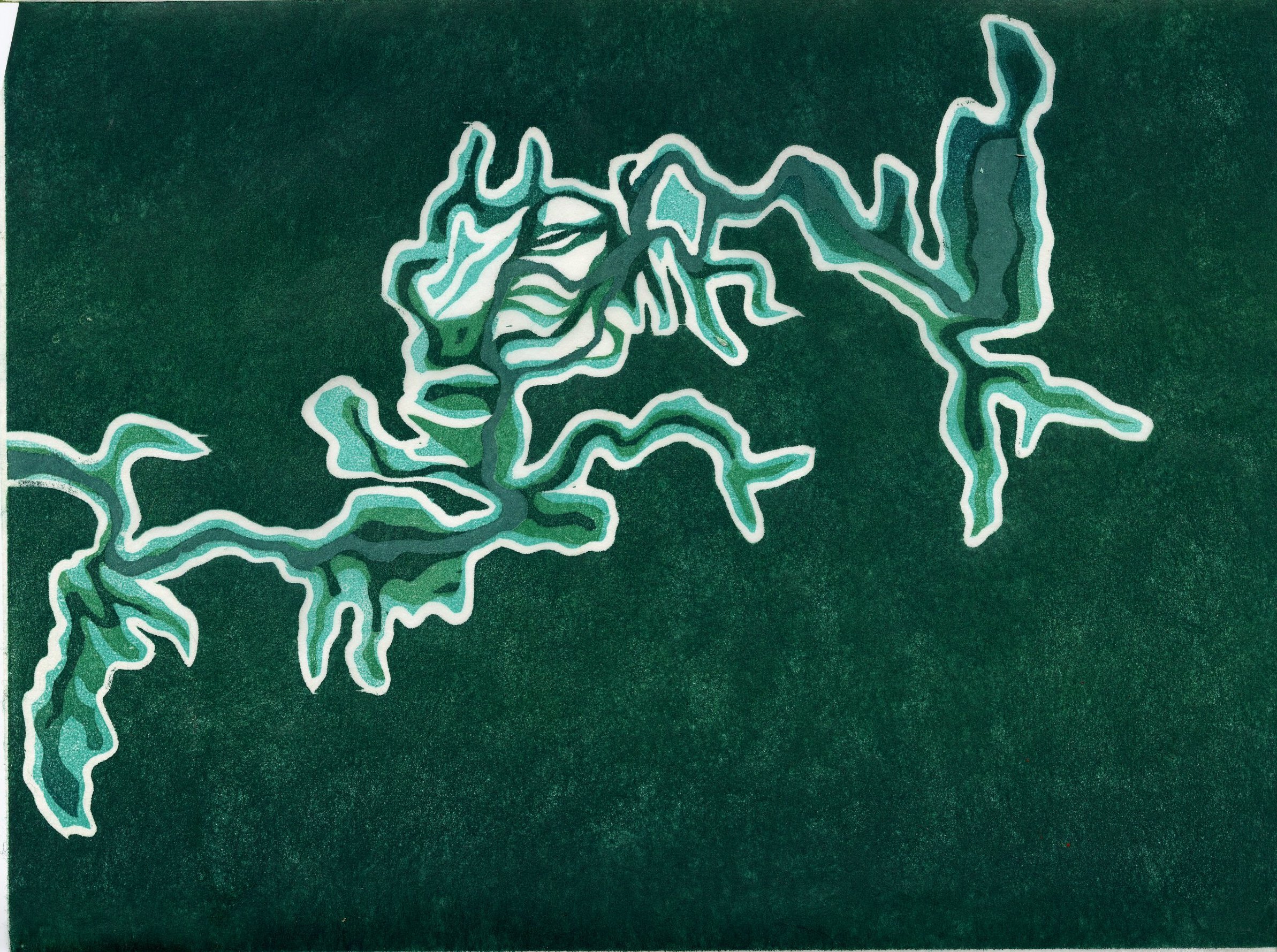

4: Andeorama

Andeorama

(made-up noun)

shorthand for “Andes Panorama,” an unbroken depiction of the Andes mountain range and a window into the question: What effect are melting glaciers having in South America?

This is a project I have been working on for the past couple of months. It has taken a lot of deliberation and exactitude to stay true to the data that inspired the visual. At the same time, I have let myself loose with certain lines of personal experience. I don’t know if this illustration can accurately be called art, or science. This process has made me think more deeply about if it is possible for work to fall into both camps.

The data:

Last year, Two Decades of Glacier Loss along the Andes, a study led by Inés Dussaillant, was published in Nature Geoscience. This research investigates the glacier mass changes in the Andes during the period 2000-2018. Later I will go into more detail depicting the regional changes, the sub periods of the study, and the downstream impacts of the glacier mass changes.

The idea:

After reading the Dussaillant paper, I thought one way to represent the extent and variety of effects that climate change has upon glacial systems in the Andes would be a lengthy illustration of the Cordillera, in the style of Alexander von Humboldt's 1807 illustration of Chimborazo and Cotopaxi. On one end would be the profile of Chimborazo, then the ridgeline would take on the shape of the Dry Andes and then the Patagonian Andes. Under this ridgeline, little titles and illustrations would depict the regional changes that Dussaillant et al identify. This illustration would combine an ode to the scientist/humanist Humboldt, who believed in the integration of art and science, with the scope of the change happening in the Andes under modern climate change.

Humboldt’s Tableau Physique (1807), a painting that captures the expansive and groundbreaking manner in which Humboldt approached studying the volcanoes of Ecuador.

In 1802, Alexander von Humboldt made the trek to Chimborazo with the help of indigenous Ecuadorian guides. Chimborazo was then believed to be the world’s tallest peak. Although a deep chasm did not allow the group to reach the summit, this expedition is notable for several reasons: it was the highest human climb in recorded history for 30 years, it depended on collaboration with the local indigenous people, it informed thinking about climate zones, and it resulted in a remarkable output of art-fused science that engaged the public. Humboldt’s Essay on The Geography of Plants includes the illustration Tableau Physique. A dramatic painting of Chimborazo and Cotopaxi is framed by detailed text. The columns contain the expeditions scientific observations of everything from barometric pressure to the presence of howler monkeys. To me, this variety of measurements is stunning in how it incorporates the full spectrum of the sciences.

Numerous drafts of Andeorama are in the works. I will create various versions in English and Spanish that highlight glacier characteristics, and the regional changes. I’ll also explain how I chose to depict some of the ecological and social impacts. Here is a sample:

Further Reading and Resources:

Fundación Glaciares Chilenos: A Chilean organization promoting the education and protection of glaciers in Chile, with some great online resources.

YaleEnvironment360 reports on: Andes Meltdown: New Insights Into Rapidly Retreating Glaciers

Glaciares de los Andes Centrales registran dramático retroceso durante la última década y perderán su capacidad de abastecer los ríos from País Circular. This article breaks down the implications in the Central Andes from the Dussaillant paper in common language (if you read Spanish!)

A striking and emotional telling of this story is told in Glacier Shallap – Or the Sad Tale of a Dying Glacier from Trans.MISSION and Erika Stockholm

2.2: Company Creek

Following Bob up Company Creek to the powerhouse intake

The Power House

Every morning, Bob Nielsen pedals up to the Stehekin Powerhouse, part of the Chelan County Public Utility District. The Powerhouse sits beside Company Creek, a few miles up the Stehekin River valley from Lake Chelan. Around the PUD complex lie trucks, cones, rain gauges, transformers and power poles. A stout second building houses more supplies. Webs of utility poles are strung overhead. Obviously, this is the nexus of Stehekin’s power supply. A two-foot diameter pipe emerging from the woods hints at the source. The pipe ducks underground into the Powerhouse, which is whirring though thick cement block walls. A gushing and frigid torrent emerges from the downstream wall of the powerhouse. Right beside the loud outflow, an ouzel (American dipper) family keeps their nest year after year. Bob suspects they have long term hearing loss.

Inside the powerhouse, a large pale green form in the middle of the room emits a great deal of noise. It’s a Pelton wheel turbine. A single jet of high pressure creekwater from the penstock shoots horizontally into cups placed along the wheel, turning the turbine.

In the control room, the walls are padded with wavy gray foam. Forest light beams into the small room through a half-open window. You can see the lower segments of the penstock outside. A monitor shows the cubic feet per second running through the pipe- 17.66 cfs. In the winter, it could be lower, around 10 cfs.

A photograph of the shrinking S-glacier over Trapper Lake hangs squarely on the wall. Bob, a who is perennial source of excellent mountaineering tales, tells me he first hiked into this area in 1981, and they had a bit of an epic because they took a route mainly over rock, not the glacier. The next time Bob passed by Trapper Lake the glacier was noticeably smaller than in 1981. Now that glacier is gone. That route once taken would be different and probably tricker now. The rocky cathedral walls above Trapper lake are barren, steep and slick. The old photograph is a haunting reminder that glaciers can become ghosts— a possibility literally casting a dimmer future for this community.

Living in a small town, Bob manages for efficiency. He strives to create reliable energy from renewable sources, minimizing the use of the backup diesel generators. He also is charged with solving power outages and keeping the power lines clear of limbs and leaves. Bob’s mission at the Powerhouse is to keep a steady amount of water running from the intake to the turbines. There are different tasks every day- in the summer there are trees and rocks to move from the streambed, in the fall there are leaves to clear from the intake grate and in the winter there are snowdrifts to shovel. The operation is running smoothly on this June morning. Water is simply obeying gravity, creek to pipe to creek, with the added benefit of passing through the Powerhouse and turning a turbine.

Bob moves actively around the Powerhouse, glancing over dials and gauges, ensuring that the electricity supply is aligned with the demand in town. About half of the power is consumed by the National Park Service. The rest goes towards powering the homes and businesses of Stehekin’s ~60 year round residents, ~200 summer residents and services for waves of summer tourists. When the hydroelectric cannot keep up with demand, a 75kw induction generator automatically starts up. This relies on a little bit of diesel to keep things running. When the flow is shut off or blocked, one of the twin 300kw backup diesel generators has to be fired up. Diesel smoke wafts through the small valley for an hour or two, and the lights stay on. A cleaner solution – a shipping container sized battery – is coming, but for now, the diesel generators serve as the backup electrical source for Stehekin. Elements of this hydroelectric system has been used sturdily since 1964, but the efficiency of the project really depends who is managing it. If Bob were less keen on advancing the sustainability and self-sufficiency of the Stehekin community, or less eager to clear leaves from the intake four times a day in the fall, a lot more diesel would be used.

The Intake

We walk alongside the penstock pipe up to the intake. Because the water for the powerhouse is drawn from within the rocky walls of a canyon, accessible only by path, everything up here is hand operated. Bob has traversed this path thousands of times, in all seasons, so he has dozens of stories to fill the ½ mile walk. We stroll beneath an underhanging mossy cliff face, across a sturdy bridge and up to the grated channel of the intake. In the channel box, some of the icy water drops down to enter the pipe. To keep enough water flowing in and around the intake area, rocks in the channel sometimes have to be broken apart and moved, particularly after large floods rearrange the channel.

In June, this creek is strong with icy blue water. Streambottom rocks are masked by the roiling current. It is loud. The torrent is amplified between canyon walls. Talking is reserved for other spaces- this is one of the creek’s place to be heard. It is also lush. Salmonberry and alder with their roots in the canyon bottom strive for light, shooting broad leaves over the water surface. The lushness of the intake is a gateway to the upstream world: where water moves wild and uncharted on its path from ice to river.

Towards a Glacier: Inhabitants

Reaching a glacier is a humbling act. Ice builds on high, cold terrain. Accessing the toe of a glacier, or even finding a good view of the ice, is often a multi-day ordeal. If you ever arrive, the ice has probably been reconfigured from the solid blob shown on your map to a fragmented or shrunken holdout of ice. Few people have reason to seek glaciers out. Runoff just happens, right? Can we even witness melting? I think that our understanding of our communities and ecosystems— and how they are affected by climate change— is hindered by this unfamiliarity with ice.

The Company Glacier sprawls across the north face of Bonanza peak, which at 9,347 feet is the tallest non-volcanic summit in the Cascade Range. As the crow flies, the glacier lies 10 miles away from where Company Creek enters the Stehekin river. Since there are only 5 miles of trail in the direction of the glacier, I know there’s no chance that I’ll reach the ice in a day. According to Bob, bushwhacking up the creek is not an efficient strategy. However, with the hours between powerhouse tour and dinnertime, I seek to encounter some of the inhabitants of the drainage and find a point where I can observe the glacier.

A birds eye view from near the summit of Bonanza Peak: The valley in the left half of the photo contains Company Creek. The glacier is unseen below and off to the left. Photo and trip report by Eric Hoffman found here.

I set out briskly uphill, but quickly I am bogged down by noting the presence of all the other beings of the Big Watershed. Bear grass washes over the thin path. A robin eggshell teeters in the duff. Rufous-colored sparrows hop between lichen covered branches. Fallen trees, even a deposit of snow from an avalanche cover the trail. While we were walking below, Bob filled the drainage with stories—of scared dogs, feline prints in snow, cougar looming over the creek. Now I’m ascending the ridge, seeing the biodiversity fan out from under me. Each step is alive with the possibility of seeing a new species combined with the risk of crushing an insect or an eggshell, and being stung by wild nettles.

In The Etiquette of Freedom, Gary Snyder says we ought to “take ourselves as no more and no less than another being in the Big Watershed”

A handmade sign hangs from the arms of a tree. Cedar Cathedral Camp. I walk down the path, and a few feet away from the gurgling Company creek, the dusky trunks of six great western red cedars rise straight up. The sky is dimmed by the spread of large, old limbs. The cedars trap cool, calming air beneath their canopy. Few plants grow in the shade apart from the calypso orchids (Calypso bulbosa) blooming in the moist and decaying soil.

“You want to be quiet in instinctive deference to the cathedral hush and because nothing you could possibly say would add a thing.” Robin Wall Kimmerer

These trees must be very old. I measure them with my wingspan – 2, 3 ¼ , 4, 4 ½, 4 ¾ arm lengths around. They range from a diameter of 4 to 8 feet at my height. Some have sweeping buttresses at the ground. The network of strong interlocking roots below this grove must be incredible. These cedars have been lapping from the Company Creek for hundreds of years. Their existence in this watershed suggests a history of reliable, favorable cedar growing climate. By the steady flow of glacier-fed Company Creek, they have outcompeted fast growing species and raised this cathedral.

“Given all cedar’s traits – slow growth, poor competitive ability, susceptibility to browsing, wildly improbably seedling establishment—one would expect it to be a rare species. But it’s not. One explanation is that while cedars can’t compete well on uplands, they thrive with wet feet in alluvial soils, swamps, and water edges that other species can’t stand. Their favorite habitat provides them with a refuge from competition” Robin Wall Kimmerer

The Watershed View

Five miles up the Company Creek trail, the stream is frothing through the bedrock in whites, grays and greens. I take photos of the water, curious if these colors are different than a creek with no glacier source. Across the bank, a winter wren bobs its sharp tail. Like the American dipper at the powerhouse, I wonder if this bird retains its hearing in the midst of glacial runoff’s roar, or if all the birds of this watershed are deaf.

I scramble 800 vertical ft up the western side of the drainage, ascending through a new mosaic of species. Seepages are crammed with pearly succulents, Columbia lewisia, Indian paintbrush and geraniums. Atop rocky outcrops, small kinnikinnick shrubs and penstemon hug the ground. I climbed up here hoping for a view of the Company Glacier, but it remains just out of view from the first bluff I reach. I scamper across a waterfall and up some very steep slopes to a second outcrop. From there, the mountain hugging-clouds part just enough to reveal the ramparts of Bonanza Peak, and amidst them, the peripheral pieces of Company Glacier. Most of the glacier is still snow covered.

The sighting comes rather anticlimactically. This is what I have been seeking for hours of moving- a blurry photo of the edge of a glacier that is still miles away- but this day has not been lost. The real magic along Company Creek – the stories filling the geographic expanse between ice and powerhouse—is dwelling in the plants and animals that you must either crane your neck upward or crouch down into the duff to observe.

Taking careful note of the watershed inhabitants has me wondering - how many of these species rely on the cold, consistent flows provided by the Company Glacier? Will they remain here in 10, 20 or 100 years, when the glacier has melted, and the north face of Bonanza peak is just a staggering wall of rock? Surely human people are not the only ones who will miss the presence of ice. Will the six cedar trees go thirsty, fall and rot away? Or will winter snowfall on the high slopes of Bonanza Peak keep enough late summer flow after the glacier has been lost? I imagine conducting a watershed census, asking each inhabitant how it will respond to future climate. That can’t happen for various reasons (how would I verify the signatures of lupine or hemlock or chipmunk #244?), but I cannot stop wondering about the differences in biodiversity between glaciated and non-glaciated creeks (spatially or temporally) in the North Cascades.

Glacier, creek, cedar, powerhouse, ouzel, river. I just spent a day following water, documenting its many forms. There is no simple explanation for where this water goes. I have just stepped through an inhabited drainage, and I know this creek is the edge of a complex and recurring pattern: in between mountaintop ice and the hydropower station along the river, the Columbia River watershed is coming alive in thousands of ways. I began my day thinking about the utility of water, from a human perspective. Now I am considering the many little spores, glands and stems that utilize water as well.

One watershed, changing with the climate. Thousands of stories both rooted and washed away.

3: Pika Story

This “chapter” is written for the story of Vivid Glacier, a climate change glacier storytelling project organized by Mauri Pelto and executed by a variety of glaciologists, explorers and wonderers. As the rest of the chapters (written from other organisms points of view) emerge, I’ll share the links.

Also, many thanks to Emily Hyde for providing details from her experience counting pikas in the high deserts of Oregon!

EEE!

Hawk circles the sky, and I sound the alarm. The other pikas hear my shriek and we all dart beneath rocks. Summer sun bares down on the talus slope where I have lived my entire life. It’s the start of an August day, the hottest time of the year.

To avoid overheating I rest in the cool shadows during the day and forage diurnally. At this time of year, I don’t have to look far to find nourishing shrubs and flowers. The alpine meadows scattered across the slope are at the peak of summer abundance. Meltwater trickles down from Vivid glacier throughout the summer, and this cold water feeds the alpine vegetation. I gather mouthfuls of thistles, fireweed and alpine grasses. Once the stems are dry, I scuttle them to caches in the rock, deep piles of collected plants called haypiles. These will feed me throughout the winter.

EEE!

I shriek again, unsure if my fellow critters can hear or understand. This is not an alarm for the presence of owl or weasel or snake. It is something more dangerous than a predator—it is a temperature warning. Of any of the inhabitants of Vivid Glacier, we know the dangers of rising temperatures the best. We pikas die if exposed to temperatures of over 78°F for too long, temperatures that the lower rock fields now reach regularly in the summer. Generations ago, my family lived at the base of this slope- but even in the shelter of the rocks, the heat became deadly. So we have climbed to cooler, higher places. Pika by pika, we are forced to establish new homes higher on the mountain.

Temperature is forcing everyone to move up- the glacier, the forest, our predators and our forage. Sometimes we move at different paces, so each season contains unpredictable risks and possibilities. Forests take root in scree slopes that once were open snow and sun. Not long ago, the talus pile where I live was covered by the cold weight of Vivid Glacier. Currently, the rocks are dry four to six months of the year and crammed with a mosaic of alpine vegetation. It’s a good home for now, but I will nose my kids up the slope when they are born. Summer temperatures keep rising, and we must too. Between here and the remnant of Vivid Glacier and the mountain top, there isn’t that much room to move. What will happen when all of the alpine life is restricted to a mountaintop? Will it become a summit of sun-bleached bones?

This is looking to be a really hot summer. What can we do? I shriek for my neighbors, but my voice feels unusually small. I hear no chirps from downslope—and I worry that my lower relatives are dying. We are powerless in the heat.

Months pass, and the air cools. I’ve survived the heat of summer and stashed away many twigs and wildflowers. Now it begins to snow, light flurries at first, and then a huge storm bring deeper drifts. Within the rocks, I sit upon my favorite haypile and the slope grows very quiet.

Unlike bear, I don’t hibernate, and unlike many of the birds, I cannot migrate. I need a thick snow blanket to insulate my home. When there is enough snow, the ground temperature is stable at 32°F, and I can survive. Without snow, winter cold can be deadly. I know that we pikas often fail to reproduce when there is not an insulative snowpack. Additionally, our favorite plants suffer frost damage and we have less to eat when melt-off begins. The talus slope is better with baby pikas and abundant forage. In solitude, I hope for plenty of snowfall, especially if this winter is a cold one. Then I scurry out to excavate an air shaft and build a tunnel to access my haypiles. Even in winter, I don’t sit still for long.

Winter passes. Under the changing surface of the snow, I have survived another season. The only place I have ever known is the alpine, where blazing summer days contrast chilly nights and even more frigid winters. In the climate of the past, we pikas were well equipped. But every year is different now. Despite our adaptions for living in the extreme reaches of the alpine, this stochasticity challenges our biological strategies. Although this winter brought plenty of snow to envelope my territory, at the bottom of the slope where my ancestors once lived, things were different. There was little snow, exposing the plants and animals to bitter cold and low moisture. The alpine meadows withered, and shrubs took their place. It seems there is no way to survive down there now.

Another change this year is the quick arrival of spring. I get moving and foraging a month earlier than my ancestors did. Springtime seems as lush as ever, yet when I look for my favorite tufts of forget-me-nots, they’re no longer there. My favorite plants migrate upslope, or disappear, and new ones march into their rootwells. All I can do is change my diet.

Over the summer, less and less water trickles down from Vivid glacier, leaving the foliage thirsty and skimpy. I stockpile what I can, preparing for the uncertain months ahead. August feels much hotter, and I get close to overheating many days. The stress and solitude fatigue me.

Below, the talus slopes in the valley are ghostly quiet. No more EEE’s! rise on the mountain thermals. There are a few more pikas above me, at the upper limit of the rock below Vivid glacier. Our population struggles to find the spot where we can survive both summer and winter temperatures and find enough to eat. We are quickly running out of space. But the temperature marches constantly upward, past where we can go.

We will climb until the heat bleaches our bones.

Heed the warning of the Pika, sentinel of Vivid Glacier.

EEE!

More:

Ecological consequences of anomalies in atmospheric moisture and snowpack by Johnston et al. 2019

Pikas versus Trump, a vengeful game/app from the Center for Biological Diversity