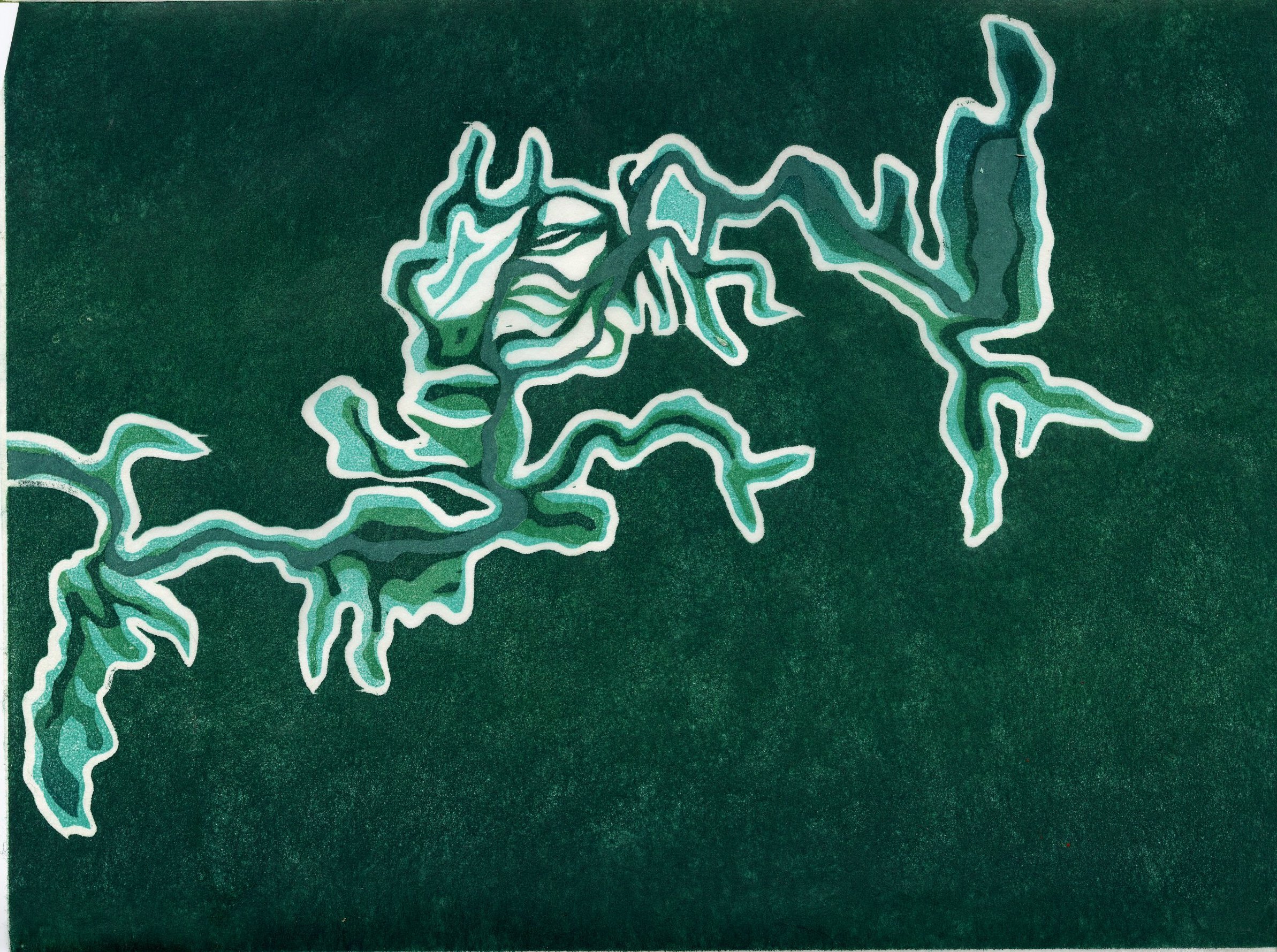

Visualizing the Range of Glaciers

This page served as a landing spot for sharing bits of my undergraduate environmental science honors thesis and related printmaking work. The North Cascades in Washington, the place I know as home, hold many glaciers that have complex ties to both ecological and human communities. Climate change is rewriting the state of these glaciers and the relationships that they can sustain. Although these connections are usually described by science, art is an expansive form of communicating a shifting landscape and its inhabitants. My project strove to explore a remarkable place in flux with various ways of knowing - scientific, personal, artistic, anecdotal. Enjoy these snippets, or download my entire thesis “Visualizing the Range of Glaciers: Science, Art and Narrative if you care to.

2.2: Company Creek

Following Bob up Company Creek to the powerhouse intake

The Power House

Every morning, Bob Nielsen pedals up to the Stehekin Powerhouse, part of the Chelan County Public Utility District. The Powerhouse sits beside Company Creek, a few miles up the Stehekin River valley from Lake Chelan. Around the PUD complex lie trucks, cones, rain gauges, transformers and power poles. A stout second building houses more supplies. Webs of utility poles are strung overhead. Obviously, this is the nexus of Stehekin’s power supply. A two-foot diameter pipe emerging from the woods hints at the source. The pipe ducks underground into the Powerhouse, which is whirring though thick cement block walls. A gushing and frigid torrent emerges from the downstream wall of the powerhouse. Right beside the loud outflow, an ouzel (American dipper) family keeps their nest year after year. Bob suspects they have long term hearing loss.

Inside the powerhouse, a large pale green form in the middle of the room emits a great deal of noise. It’s a Pelton wheel turbine. A single jet of high pressure creekwater from the penstock shoots horizontally into cups placed along the wheel, turning the turbine.

In the control room, the walls are padded with wavy gray foam. Forest light beams into the small room through a half-open window. You can see the lower segments of the penstock outside. A monitor shows the cubic feet per second running through the pipe- 17.66 cfs. In the winter, it could be lower, around 10 cfs.

A photograph of the shrinking S-glacier over Trapper Lake hangs squarely on the wall. Bob, a who is perennial source of excellent mountaineering tales, tells me he first hiked into this area in 1981, and they had a bit of an epic because they took a route mainly over rock, not the glacier. The next time Bob passed by Trapper Lake the glacier was noticeably smaller than in 1981. Now that glacier is gone. That route once taken would be different and probably tricker now. The rocky cathedral walls above Trapper lake are barren, steep and slick. The old photograph is a haunting reminder that glaciers can become ghosts— a possibility literally casting a dimmer future for this community.

Living in a small town, Bob manages for efficiency. He strives to create reliable energy from renewable sources, minimizing the use of the backup diesel generators. He also is charged with solving power outages and keeping the power lines clear of limbs and leaves. Bob’s mission at the Powerhouse is to keep a steady amount of water running from the intake to the turbines. There are different tasks every day- in the summer there are trees and rocks to move from the streambed, in the fall there are leaves to clear from the intake grate and in the winter there are snowdrifts to shovel. The operation is running smoothly on this June morning. Water is simply obeying gravity, creek to pipe to creek, with the added benefit of passing through the Powerhouse and turning a turbine.

Bob moves actively around the Powerhouse, glancing over dials and gauges, ensuring that the electricity supply is aligned with the demand in town. About half of the power is consumed by the National Park Service. The rest goes towards powering the homes and businesses of Stehekin’s ~60 year round residents, ~200 summer residents and services for waves of summer tourists. When the hydroelectric cannot keep up with demand, a 75kw induction generator automatically starts up. This relies on a little bit of diesel to keep things running. When the flow is shut off or blocked, one of the twin 300kw backup diesel generators has to be fired up. Diesel smoke wafts through the small valley for an hour or two, and the lights stay on. A cleaner solution – a shipping container sized battery – is coming, but for now, the diesel generators serve as the backup electrical source for Stehekin. Elements of this hydroelectric system has been used sturdily since 1964, but the efficiency of the project really depends who is managing it. If Bob were less keen on advancing the sustainability and self-sufficiency of the Stehekin community, or less eager to clear leaves from the intake four times a day in the fall, a lot more diesel would be used.

The Intake

We walk alongside the penstock pipe up to the intake. Because the water for the powerhouse is drawn from within the rocky walls of a canyon, accessible only by path, everything up here is hand operated. Bob has traversed this path thousands of times, in all seasons, so he has dozens of stories to fill the ½ mile walk. We stroll beneath an underhanging mossy cliff face, across a sturdy bridge and up to the grated channel of the intake. In the channel box, some of the icy water drops down to enter the pipe. To keep enough water flowing in and around the intake area, rocks in the channel sometimes have to be broken apart and moved, particularly after large floods rearrange the channel.

In June, this creek is strong with icy blue water. Streambottom rocks are masked by the roiling current. It is loud. The torrent is amplified between canyon walls. Talking is reserved for other spaces- this is one of the creek’s place to be heard. It is also lush. Salmonberry and alder with their roots in the canyon bottom strive for light, shooting broad leaves over the water surface. The lushness of the intake is a gateway to the upstream world: where water moves wild and uncharted on its path from ice to river.

Towards a Glacier: Inhabitants

Reaching a glacier is a humbling act. Ice builds on high, cold terrain. Accessing the toe of a glacier, or even finding a good view of the ice, is often a multi-day ordeal. If you ever arrive, the ice has probably been reconfigured from the solid blob shown on your map to a fragmented or shrunken holdout of ice. Few people have reason to seek glaciers out. Runoff just happens, right? Can we even witness melting? I think that our understanding of our communities and ecosystems— and how they are affected by climate change— is hindered by this unfamiliarity with ice.

The Company Glacier sprawls across the north face of Bonanza peak, which at 9,347 feet is the tallest non-volcanic summit in the Cascade Range. As the crow flies, the glacier lies 10 miles away from where Company Creek enters the Stehekin river. Since there are only 5 miles of trail in the direction of the glacier, I know there’s no chance that I’ll reach the ice in a day. According to Bob, bushwhacking up the creek is not an efficient strategy. However, with the hours between powerhouse tour and dinnertime, I seek to encounter some of the inhabitants of the drainage and find a point where I can observe the glacier.

A birds eye view from near the summit of Bonanza Peak: The valley in the left half of the photo contains Company Creek. The glacier is unseen below and off to the left. Photo and trip report by Eric Hoffman found here.

I set out briskly uphill, but quickly I am bogged down by noting the presence of all the other beings of the Big Watershed. Bear grass washes over the thin path. A robin eggshell teeters in the duff. Rufous-colored sparrows hop between lichen covered branches. Fallen trees, even a deposit of snow from an avalanche cover the trail. While we were walking below, Bob filled the drainage with stories—of scared dogs, feline prints in snow, cougar looming over the creek. Now I’m ascending the ridge, seeing the biodiversity fan out from under me. Each step is alive with the possibility of seeing a new species combined with the risk of crushing an insect or an eggshell, and being stung by wild nettles.

In The Etiquette of Freedom, Gary Snyder says we ought to “take ourselves as no more and no less than another being in the Big Watershed”

A handmade sign hangs from the arms of a tree. Cedar Cathedral Camp. I walk down the path, and a few feet away from the gurgling Company creek, the dusky trunks of six great western red cedars rise straight up. The sky is dimmed by the spread of large, old limbs. The cedars trap cool, calming air beneath their canopy. Few plants grow in the shade apart from the calypso orchids (Calypso bulbosa) blooming in the moist and decaying soil.

“You want to be quiet in instinctive deference to the cathedral hush and because nothing you could possibly say would add a thing.” Robin Wall Kimmerer

These trees must be very old. I measure them with my wingspan – 2, 3 ¼ , 4, 4 ½, 4 ¾ arm lengths around. They range from a diameter of 4 to 8 feet at my height. Some have sweeping buttresses at the ground. The network of strong interlocking roots below this grove must be incredible. These cedars have been lapping from the Company Creek for hundreds of years. Their existence in this watershed suggests a history of reliable, favorable cedar growing climate. By the steady flow of glacier-fed Company Creek, they have outcompeted fast growing species and raised this cathedral.

“Given all cedar’s traits – slow growth, poor competitive ability, susceptibility to browsing, wildly improbably seedling establishment—one would expect it to be a rare species. But it’s not. One explanation is that while cedars can’t compete well on uplands, they thrive with wet feet in alluvial soils, swamps, and water edges that other species can’t stand. Their favorite habitat provides them with a refuge from competition” Robin Wall Kimmerer

The Watershed View

Five miles up the Company Creek trail, the stream is frothing through the bedrock in whites, grays and greens. I take photos of the water, curious if these colors are different than a creek with no glacier source. Across the bank, a winter wren bobs its sharp tail. Like the American dipper at the powerhouse, I wonder if this bird retains its hearing in the midst of glacial runoff’s roar, or if all the birds of this watershed are deaf.

I scramble 800 vertical ft up the western side of the drainage, ascending through a new mosaic of species. Seepages are crammed with pearly succulents, Columbia lewisia, Indian paintbrush and geraniums. Atop rocky outcrops, small kinnikinnick shrubs and penstemon hug the ground. I climbed up here hoping for a view of the Company Glacier, but it remains just out of view from the first bluff I reach. I scamper across a waterfall and up some very steep slopes to a second outcrop. From there, the mountain hugging-clouds part just enough to reveal the ramparts of Bonanza Peak, and amidst them, the peripheral pieces of Company Glacier. Most of the glacier is still snow covered.

The sighting comes rather anticlimactically. This is what I have been seeking for hours of moving- a blurry photo of the edge of a glacier that is still miles away- but this day has not been lost. The real magic along Company Creek – the stories filling the geographic expanse between ice and powerhouse—is dwelling in the plants and animals that you must either crane your neck upward or crouch down into the duff to observe.

Taking careful note of the watershed inhabitants has me wondering - how many of these species rely on the cold, consistent flows provided by the Company Glacier? Will they remain here in 10, 20 or 100 years, when the glacier has melted, and the north face of Bonanza peak is just a staggering wall of rock? Surely human people are not the only ones who will miss the presence of ice. Will the six cedar trees go thirsty, fall and rot away? Or will winter snowfall on the high slopes of Bonanza Peak keep enough late summer flow after the glacier has been lost? I imagine conducting a watershed census, asking each inhabitant how it will respond to future climate. That can’t happen for various reasons (how would I verify the signatures of lupine or hemlock or chipmunk #244?), but I cannot stop wondering about the differences in biodiversity between glaciated and non-glaciated creeks (spatially or temporally) in the North Cascades.

Glacier, creek, cedar, powerhouse, ouzel, river. I just spent a day following water, documenting its many forms. There is no simple explanation for where this water goes. I have just stepped through an inhabited drainage, and I know this creek is the edge of a complex and recurring pattern: in between mountaintop ice and the hydropower station along the river, the Columbia River watershed is coming alive in thousands of ways. I began my day thinking about the utility of water, from a human perspective. Now I am considering the many little spores, glands and stems that utilize water as well.

One watershed, changing with the climate. Thousands of stories both rooted and washed away.

2.1: Going to Stehekin

On Monday, June 15th, I left the Methow Valley and traveled to Stehekin, Washington. Here are early observations and reflections from the first stages of this trip.

The Great River: Columbia

Your power is turning our darkness to dawn

So roll on, Columbia, roll on

Woody Guthrie

On the banks of the Columbia River in North Central Washington, powerlines loom above ordered rows of apple trees and grape vines. Diagonal, vertical, a valley remade by thin lines. The river too becomes a line, a horizon. On the surface the Columbia looks motionless, her flow imperceptible. This languid river straddles the center of the valley, bisecting the tidy tiles of orchardry.

Hydropower and irrigation water are drawn from this great river, all throughout Washington State. This feeds the region’s growth and agriculture. With enough water, this is the ideal climate for apples.

I am looking into the valley where Chelan enters the Columbia. This is the land of the Chelan people. Downstream of here, the river is stoppered behind eight different dams: Bonneville, The Dalles, John Day, McNary, Priest Rapids, Wanapum, Rock Island, Rocky Reach. Upstream and damming the tributaries there are dozens more. Between dams, the river looks motionless. Yet inside the squat concrete dams, the water turns massive turbines and generates enormous amounts of electricity. One current transforms into another, powering lightbulbs, offices, microwaves and apple packing plants.

The scale of the Columbia River watershed and her hydropower generation is massive, nearly incomprehensible. The sheer size of one dam is overwhelming in person. Picturing the system that coordinates each concrete structure and kilowatt hour generates an abstract sense of scale. This view leaves many important small things unspoken. I’m interested in tracing the stories of the tributaries, the individuals and the water sources that feed into the larger story. I’m going to a small fraction of the Columbia River basin—one that is familiar, glacier fed, a bit easier to understand. To begin, I am getting on a boat.

The Long Lake: Tsi-laan

A settler named Ella Clark recorded this creation story from the Chelan nation: when Coyote came to the animal people along the Chelan River, he said to them, “I will send many salmon up your river if you will give me a nice young girl for my wife.” But the Chelan people refused. They thought it was not proper for a young girl to marry anyone as old as Coyote. So Coyote angrily blocked up the Canyon of Chelan River with huge rocks and thus made a waterfall. The water dammed up behind the rock and formed Lake Chelan. The salmon could never get past the waterfall. That is why there are no salmon in Lake Chelan to this day.”

I arrive on the Lake Chelan ferry dock for the 8:30 am boat to Stehekin. This ribbon of deep, cold water is 50 miles long and 1,485 feet deep at its lowest point – nearly 400 feet below sea level. The Lady Express motors northwest, beelining through the widest (2 miles) and narrowest (1/4 mile) sections of the lake. We quickly pass the agricultural communities and enter the reaches of undeveloped lakeshore. I scan the rocky cliffs for bighorn sheep but see none. Uplake, hiking trails and campgrounds dot the shoreline at long intervals.

Since the last ice age, when this lake is thought to have formed, this landscape has been changing. Lake Chelan was raised 21 feet in 1927 with the construction of the Lake Chelan Dam, a Chelan county hydropower project that provides Chelan and nearby communities with power. This area has some of the cheapest electricity rates in the country- residential rates are about 3¢ per kilowatt hour. For comparison, Seattle is around 11¢ per kWh, and New York City is 20¢ per kWh.

The level of the lake fluctuates seasonally as the Chelan County Public Utility District (PUD) makes room for spring runoff and allows water to pass through the turbines, spill into the tailrace, and enter the Columbia. During winter at the Stehekin end, low water levels expose mudflats that become snow covered. Spring warmth melts the snow and ice cradled in the mountains. The runoff raises the lake to its full green depth, making it sailboat-worthy by June. Nearly every summer afternoon a small crew headed by a man named Bob navigate a wooden sailboat called Ipsut around the head of the lake. Rough cliffs and forests loom high above. They tack back and forth, dodging stumps from days when the lake was lower, and tree trunks deposited by the Stehekin River.

The Wild River: Stehekin

Bob and Tammy live on the bank of the Stehekin River where it enters Lake Chelan. Just steps away from their living room, the river sings and flows. Three thousand cubic feet of June snowmelt glide by their house every second, refracting every possible shade of green.

This place becomes a passage for many things, and to live here is to be a listener. At night, rushing water rinses through dreams. During floods, stones knock against each other underwater. Every morning, hoots and chirps fill the air as all kinds of birds take wing above the river, using it as a passageway. Logs and sticks drift by and come to rest in the lake, building a web of wood on the delta. Wind settles down river and rustles the maple leaves. Sediment passes by. You can sense the geologic processes of erosion and deposition taking place, season after season. Bob and Tammy’s house is so close to the water you can close your eyes and hear precarity. In a geologic sense, this is an unlikely structure. So, to live here is to have a stake in the watershed, a willingness to live in the company of torrents, torpedoing logs and transient green water.

Bob and Tammy tell me their story of the October 2003 flood, when days of mountain snowfall and a rainstorm precipitated a 20,000 cfs flood that turned their home into an island and their yard into a kayak pool. As the lake filled up, it backed up towards their house, surrounding them with slow deep water. With three boys at home, they pulled propane tanks from the flood and tried to keep cars from floating away. The family watched as telephone pole height firs were wrenched out of the river and into the forest above their house.

One combination of weather events has the force to completely rearrange a dwelling place. Around Bob and Tammy’s, the 2003 flood stripped the beaches from the river banks and rearranged the rocks in the channel. Once, there was room for a parking lot between the river and their house. Now there is just a six-foot strip of grass and daisies. They know that the next flood could remake it all over again.