1: Carver Lake

With this post I am test driving this glacier-research-art blog and how I will document and process my work this summer. My summer research project will become a part of my environmental science honors thesis.

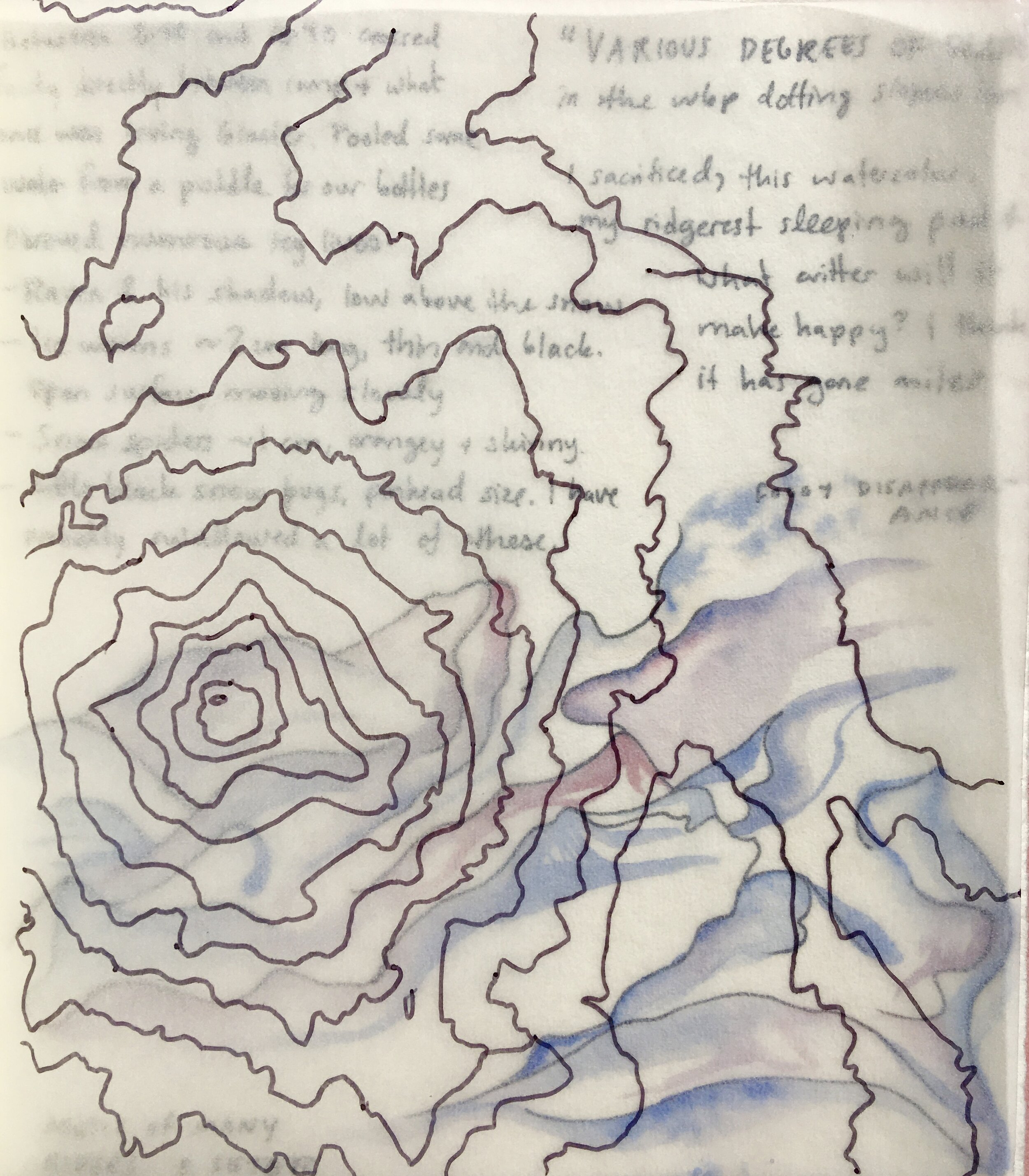

Collages of topography tracings, Carver Lake bathymetry, photos by Olivia Moehl, and watercolor journal pages.

Location: 44° 6'53.39"N. 121°44'44.84"W.

Local time: 5:41 am, 25th of May, 2020.

Cause of awakening: Sunlight seemingly rupturing the seams of the tent.

Company: My good friend Olivia, some instant mashed potatoes, and skis.

We are just waking up in a tent set on the East slope of South Sister, a volcano in the Three Sisters Wilderness of Central Oregon. Outside our zippers, the dawnsun blazes long blue shadows from the whitebark pine krummholz stands. Fog curls off the summits of Middle Sister and North Sister, resplendent in the early sky. After completing a pot of oatmeal and a watercolor painting, we pluck our drying skins from the arms of whitebark pine, smooth them onto our skis, and begin our glide north.

Our morning is spent exploring the wide, wonky saddle between South and Middle Sister, a landscape defined by hollows and surges. Everything but the crests of the moraines is filled with pure white snow. We weave between the snow-veiled Chambers Lakes and up to around 8,700 feet on Middle Sister. Then a cloud surrounds us. We have less than 100 feet of visibility. We descend back to the saddle and cross over to South Sister, where it is clearer. Winding upward through a new series of moraines and snowfields, we arrive at the base of South Sister’s eastern headwall.

A few hundred feet below us, we see a flat snowy plain, the signature of a wintry alpine lake. It is quietly snow covered, aside from a thin crescent of blue slush. This is Carver Lake, at 7,800 feet on the east face of South Sister. Surface area: 15.4 acres. Estimated volume: 740 acre feet. Carver pools deeply behind a loose, unvegetated moraine with distinctly pointy peaks. We could see these uprisings for miles although Carver Lake has remained invisible except from this Prouty glacier bowl.

Camp on the east face of South Sister. The peaks in the distance are Middle Sister on the left and North Sister on the right.

Moraines and lakes on the saddle between Middle and North Sister. On the right is one of the small Chambers Lakes, mostly covered in snow.

Viewing Carver Lake from above.

A snowfield slopes into the lake from the left.

A pyramidal moraine lies to the right of Carver’s outlet stream.

In 1987, researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey investigated the possibility for the glacial moraine holding back Carver Lake to fail. The precedent for researching this were three historical glacial moraine dams of the Sisters Range bursting in 1942, 1966 and 1970. Triggered by ice fall, some of those lakes emptied completely, and all caused large-magnitude floods affecting downstream communities. The authors write that due to the evidence of past breaches and floods,

“the frequency of breakouts of moraine-impounded lakes in the Three Sisters area can be considered to be greater than about one every 15 to 20 years (an annual probability of at least 5 to 6 percent) until moraine lakes in the area no longer exist).” (Laenen et al., 1987)

Few of these moraine lakes in Oregon are well studied, but researchers assume that the likelihood of any one lake failing is 1 percent a year. Of Carver lake they say,

“The topographic setting of the lake at the base of steep unstable masses of ice, snow, and rock, as well as the complete drainage of other moraine-dammed lakes in the area, clearly indicate that Carver Lake dam could fail catastrophically.”

If the lake were destabilized, there could be a catastrophic flood. This would theoretically be triggered by seismic activity and an avalanche or rockfall from the glacier and cliffs hanging above Carver Lake. Under an extreme scenario, ten-foot waves would swish across the lake and break the moraine dam, draining the entire volume of the lake within three minutes. The flood would swell to a magnitude ten times greater than a 1% probability meteorological flood. It would accumulate readily erodible glacial material in the steep Whychus creek channel, and double in volume over its first eight miles. At maximum discharge, the flow would be 180,000 cubic feet per second. Less than two hours after the avalanche, upon reaching the town of Sisters, Oregon, the flow would have debulked considerable amounts of sediment (up to 6 feet thick on the valley flats) but still could carry up to 9,800 cubic feet per second.

It wasn’t until we linked Prouty glacier to Carver Lake and then skied directly down from the lake to our camp that we realized how close to this looming hazard we were sleeping. To be sure, the calculations may have shifted since 1987: the gentle ice-free slope above Carver Lake on this May day did not seem to contain considerable avalanche risk. Many moraine dams fail within their first 20 years, and Carver appeared somewhere around 1930. However, it is pretty riveting to imagine the worst-case scenario. We would certainly be the first inundated or entombed casualties. Olivia and I live with strong links to mountainous terrain- she is a geologist; we both sketch, ski and study these places. By nature, our interests are bound to environmental losses and risks.

What is risk?

Is it camping beside a moraine that has a one percent chance of failing in a year?

Is it the act of exploring the unknown side of the mountain?

Is it letting ourselves love something that is melting?

I feel like I am riding the crest of a wave of environmental change. When I read, when I look underfoot, I see more loss. The more my awareness grows, the higher up I am pushed up on the wave; the more disasters, risks and injustices feed the wave. Historical patterns are ruptured by the wave. Assumptions dissolve. It’s almost impossible to find a balance point. The wave seems to tug at all lives, all places, all histories. Trying to build a sense of place during my lifetime is an exercise in constant change and adaptation. Meltwater loosens my grip on every solid thing.

The more I try to understand, the more I risk losing.

Still, I am pulled into the landscape of glaciers, mountains and rivers. This summer, I am diving in. I know that these things will change irreversibly within my lifetime. Glaciers will disappear. Gravity-hungry meltwater may the break moraines I have slept next to. I will share my summer with risk, with knowing what is changing and doing my best to share that. I don’t know what may become of my work, but I hope to at least raise awareness, which can be an attack on how we live our lives, combatting complacency towards climate change.

My relationship to the mountains is personal. It is through breathing mountain air, eddying into waterfalls and sweating buckets as I traverse folds of rock that I connect to mountains. I do not always think inside the rational forms of environmental science, but they are a very good tool. For observing and experimenting. Art is another tool. For remembering and imagining. I have dreams for this project, that I may use this trio of tools—science, art and alpinism-- to create something of meaning and importance. Now I will begin, writing, studying and creating.

Because,

We are losing glaciers.

We are losing a special, storied hue of blue.

Water gathers in deepening lakes, lakes that may burst and rush downstream.

We live downstream. We drink the glacier water.

The water within us was once ice.

Unlike the thicket-like peaks of the North Cascades, from the Sisters I look directly down to town. Water melts, collects in streams, feeds fields and waters people. In the crisp central Oregon air, these links are crystalized. 48 hours without seeing a stranger or a screen create space for reflecting and exploring deeply.

Yet this altitude also carries privilege. I have the time, resources and money to travel to remote places in the mountains. If glaciers melt, my life may lose meaning, but I will not lose my life. There are other people who bear much graver impacts of glaciers melting and eroding- people who likely do not have the resources to climb up to see the glaciers. The fields of science, conservation, glaciology and mountaineering have roots that are socially and culturally problematic, issues that still linger today.

As I enter this work, I commit to addressing the social dimensions of climate change in the best way I know how: using the tools of art and science to shape appreciation and concern for the changing environment, illuminating the people and places that struggle to make their voices heard.

More tidbits! A couple of the threads that link to everything else:

HISTORY

I’ve been fascinated with GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods) since reading the book In the shadow of melting glaciers : climate change and Andean society by Mark Carey a few months ago.I had no idea that avalanche triggered GLOFs in the Cordillera Blanca took so many lives. In 1941, one GLOF devastated Huarez Peru, killing 4,000 people. The disasters also instigated many political and engineering projects, including a state glaciology unit charged with mitigating the hazards of GLOFs.In the Andes, as in the Cascades, climate change has melted glaciers, creating large glacial lakes below. Often the dams restricting the outflow of these lakes are merely loose deposits of rock the glacier once carried -- moraines. When an avalanche or rock slide (other events potentially increased in frequency/scope by anthropogenic climate change) hits the lake, the dams may burst. After reading about these catastrophes in the Andes, I was surprised to find myself so close to one.

WHITEBARK PINE

Whitebark pine are high-elevation guardians of snow. Up on South Sister, they protect long loaves of snow from the wind. These banks melt later than unsheltered snow, protracting mountain runoff. High elevation whitebark pine, or glacier wastage: two important and declining sources of late summer runoff. They’re incredibly tough trees, and it was a joy to camp among their wizened forms.