Dancing on Your Lovely Bones:

An Ode to Western Red Cedar

Artists note: This work is an exploration of printmedia and writing linked to place. It is a poetic history of trees and people. The subject is the Pacific Northwest and the patterns of change that affect life in this rich, wild part of the world. The various artworks were created over the course of four semesters of printmaking study. The intaglio piece Dancing on Your Lovely Bones provided the kindling for the writing project. Nature philosophy texts, poems about working the wilderness of the Northwest, and my experience researching Maine’s forests in January of 2019 provided additional inspiration. Many thanks to my professors at Colby who have encouraged me to explore the topics of environmental humanities, forests in times of climate change, and storytelling:

Justin Becknell Forest ecology

Rory Bradley German nature philosophy

Amanda Lilleston Printmaking

Brooke Williams Environmental storytelling

This piece won the 2019 Buck Prize for student communication about climate change and was featured by the Colby Climate Project in the spring of 2019.

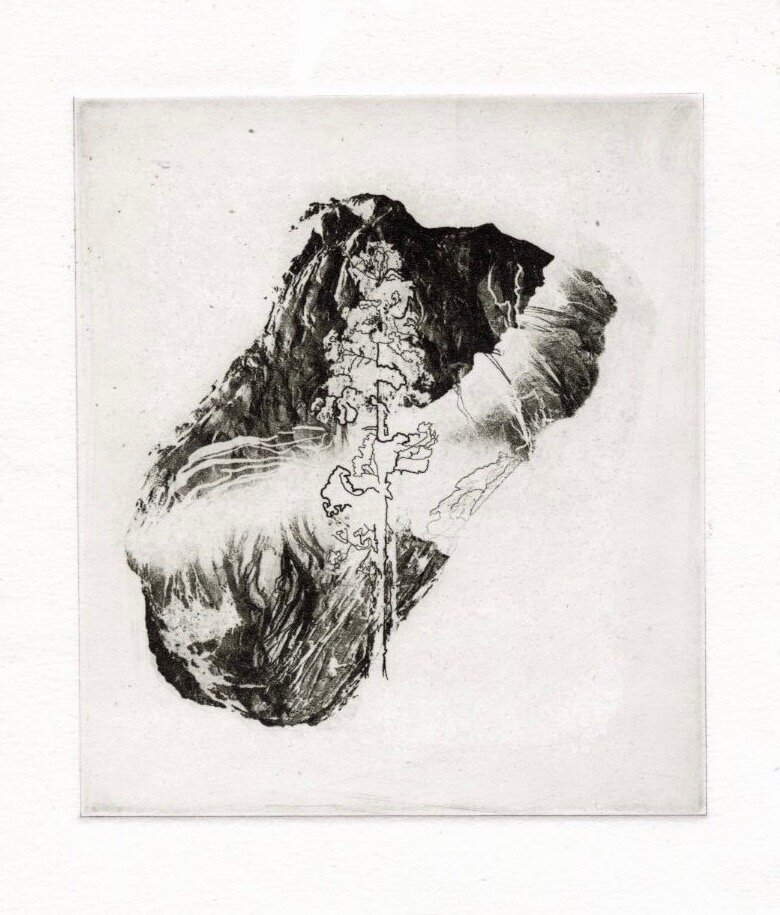

Cal Waichler, Dancing on Your Lovely Bones, intaglio stepetch and drypoint, 2019

Sometime on my journey home, the jet approaches the tarmac at the Seatac airport.

Looking out, I gather fog, topography, greenery. Seattle is growing. Acres of asphalt roll out the land. The furrows and piled moraines from the Vashon Glacier have been filled in, carved out. The tide flats are forgotten under spreads of gravel. Hills sink with the weight of human history and an overstory of glass and steel. Water moves through a circuitry of pipes, locks and canals. Today even the wild rivers are hemmed by concrete when they taste their first salt from the Sound.

I’m thinking about how SeaTac airport levels 2,500 acres when I’m jolted by the very texture of the land. As the wheels grab home ground, the jet, my body and the passenger seat all rush forward, but my mind goes rushing into the past.

What existed before this?

Before the rushing dusky rivers were dammed and the forests of Cascadia were felled? Before the spiky verdant carpet of the hills was slipped into slender 2x4s and shuttled off in railroad cars? Before the first settler left a single footstep in this deep rich soil? When nothing compromised the texture of this land?

Cal Waichler, Alerce, polyester plate intaglio, 2018.

Imagine it.

I am whirled away into a tiny green cedar cone, a millennium back. Yellow pollen merges with my scales and over three short years, my body turns brown and purple and falls into a patch of damp duff. In a stroke of luck, the shade and the moisture are perfect and I sink in, extending downward and upward with innate vigor.

Over hundreds of years, my small sap-and-needle soul grows into a giant. I am Thuja plicata, Arborvitae. Ancient and branched and now dying, like Latin itself. Older than the history we can imagine. The tree of life.

Every form of this tree is a link to the world. My needles look like they are braided, and they are, to the damp air and the sunlight they convert to sugar. My curving branches balance bird nests and filter the wind. My roots are deep and link with my neighbors. We shuttle nutrients and signals through our forest, building resiliency. Every surface that unfolds is populated by fungi, lichens, insects, a dizzying array of life. Place all of these forms together, and there is brilliance in the habitat generated, the climate created. I do not exist as one tree: I am a superorganism. The forest network both creates and benefits from shelter, shade, moisture and food. This is where we should begin to learn.

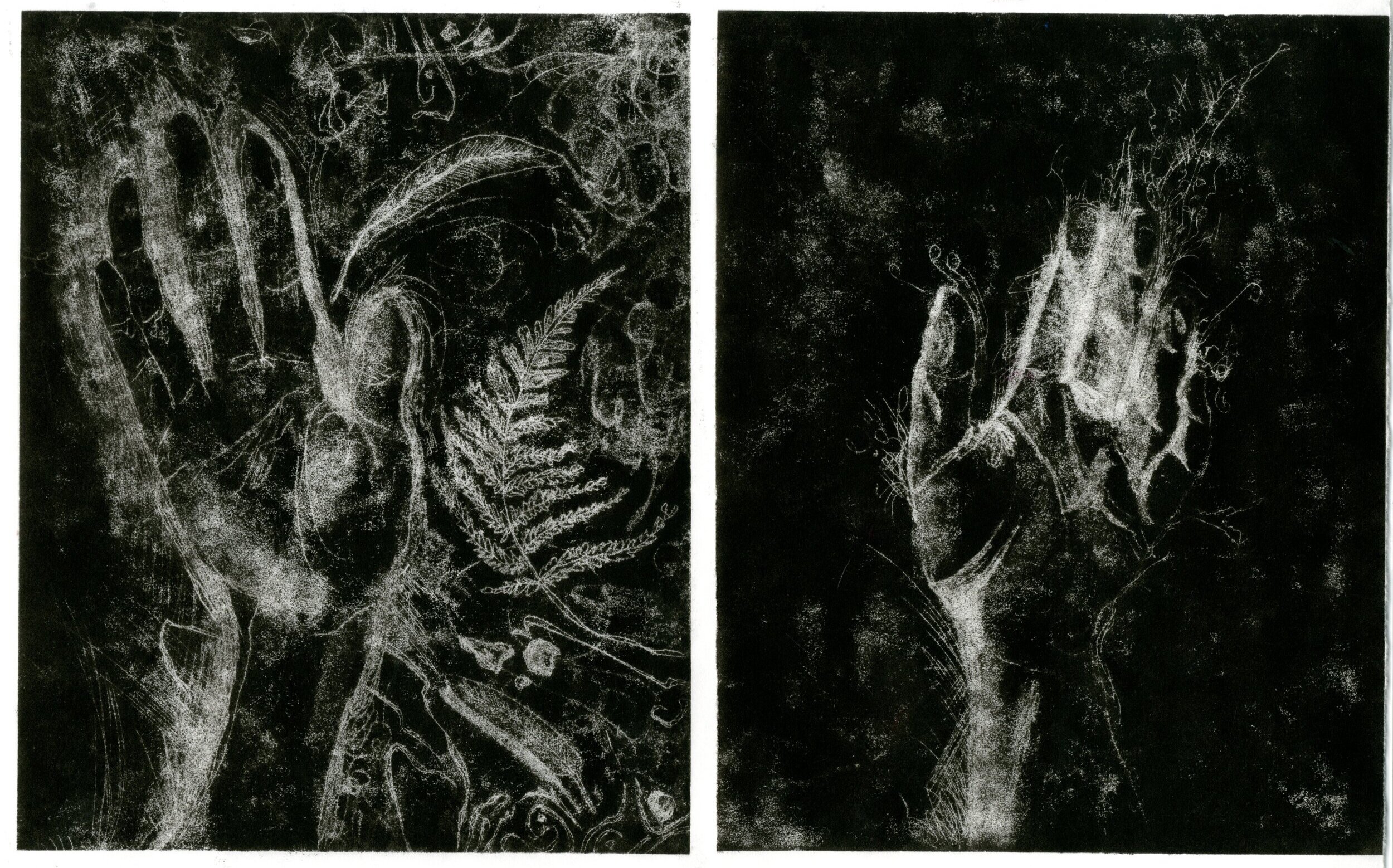

Cal Waichler, Scars, intaglio hardground, soft ground and soap ground, 2018

There is a sibling of mine across the Sound that will grow to 142 feet and raise a hundred-foot hemlock inside her hollowed-out passages. Another will amass 15,300 cubic feet of wood before her death. There are uncounted others that will fill twenty-foot diameter trunks. The steady pull of xylem elevates water and nutrients, generating some of the greatest biomass on earth.

We share the wealth of our communities with the People of the Inside. They give new life to our bones as they turn a few of us into long canoes, our planks into longhouses, our bark into baskets and fishing line. Just as one cedar sustains a community of living things, the Indians gather an environment to sustain them. They call us cedars the Long Life Makers. They understand that in one lifetime, we support thousands of others. We have lines of connection to all of the living things around us. These links are corridors for magic to travel. That is our gift.

Cal Waichler, Wild Mercy, trace monotype, 2017

An earthquake shatters Cascadia in the year 1700. The Juan de Fuca plate collides with the crust of North America, sending tremors into the forest. That season, the trees grow warped rings. Centuries later, those anomalies in my grain prompt paleoclimatologists to study my stump, to get to know me as a seismometer and a knower of rainfall. They find swollen years that tell of rainstorms soaking the foothills, and shrunken rings that illuminate times of frost. They even discover ancient volcanic eruptions, skies of ash. No wonder they will make paper books from my flesh. It is already steeped in stories.

In the year I turn 800, the first white people traipse through our forest cathedral. At first, they struggle against the pattern of the land but they soon learn to revise it for wagons, then boxcars. Then, with crosscut saws and company orders, the forest becomes a resource. The old currency of light is forgotten, and a new system of cash and fuel is instated.

Everyone quickly forgets that trees and humans share one nature. The connection, awareness and responsibility we used to share burns away in the first clear-cut slash pile. The gesture of the woods loses its reciprocity.

Cal Waichler, Untitled, lithograph, 2018

For years I have heard the echoes of extraction throughout the hills. In the year 1898, I myself am approached by axehandles and four men who are fluent in steel and sweat. They speak a new west coast vernacular, blunt and honest. They cut down great trees not because it is in their individual nature but because they must. I cannot blame them. In the destiny they have been taught, blood must be spilled, and old growth ought to be liquidated. Their innate giving language has been displaced by the deafening scream of economy and job and necessity.

Clap of thunder. As the sunlight world rushes upward, I go rushing down. I grasp home ground with the force of a million interconnected organisms. When the needles and duff finally settle, there is stillness.

It took three days to cut me down. Five weeks to move my skeleton. Death is not my end, though. If the forest embodies anything, it is not beginnings nor ends, but middles. Decay powers the cycling of nitrogen and phosphorous and macronutrients. My roots share carbon and energy with the trees around me: the community goes on.

Cal Waichler, Untitled, linocut, 2017

A stump. The people take me as I am. They don’t dwell on the absence in the forest but embrace what is now present. Soft strong lumber fuels their fabrications. Under the intoxication of manufacturing railroad ties and inhabiting sweeps of new houses, it is easy to forget about roots.

The soles of their dancing shoes tap my flattened base. A beautiful violin hewn from fine-grained yellow wood lulls them in their waltz upon my bones.

The song of loss is harrowing.

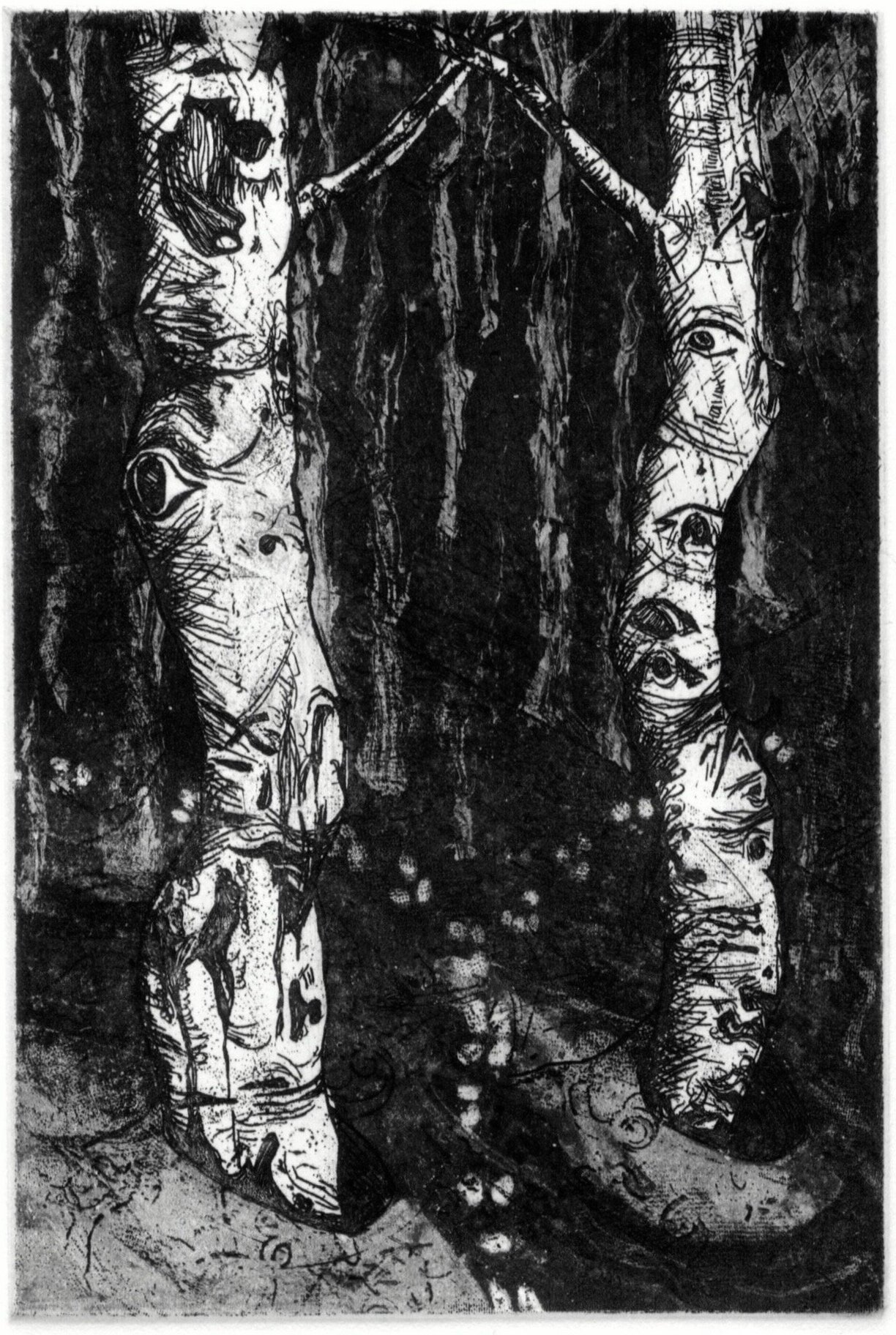

Cal Waichler, Forêt, hardground, 2018

Pass the Talking Stick

Another turn to speak, from one who also must grow, respire, reproduce and die. One who needs water, carbon, minerals, and oxygen to survive. One who has the privilege of putting words on your pages.

We have lost sight of the forest. We began analyzing it by parts and board feet and lost the truth of the forest– it isn’t a collection of individual trees or a crop, but a trembling web of life. After plucking the delicate strings of this web for centuries, the shade of the understory has been fractured. Salamanders are banished. Habitat is razed. The torn ground washes away and muddies the gills of the fish. With the infinite splintering of a falling goddess, the links are severed. It isn’t easy to grow back.

As more trunks fall and fuel the human economy, carbon, once so impressively inscribed in living towers, enters the atmosphere. Without habitat, animal populations become ghosts of what they once were. Climate changes in the Pacific Northwest. The habitat for the western red cedar shifts northward, the direction of cool and wet. But a tree does not know how to move. Their finest lesson becomes their fatal flaw—they are experts in standing still.

How do we mend the relationship between trees and people?

First, we should walk into a forest formed by very big trees. Tall trunks will remind us of how small and young we are. Sheltered by Arborvitae, we can practice patience and listening and observation, training ourselves to sense the silent lessons of trees. It will be helpful to seek teachers who understand reciprocity, who may teach us the cedars’ life-long code of giving. They will show us that trees and people can speak to one another through the dialect of gratitude. The benefits of this connection will range from shelter and oxygen to healing and awe. We must immerse ourselves in the forest’s web if we wish to understand how we may help it grow back. We should hold ourselves open to both data and art, allowing our tools of knowing to be unlimited. If we can reclaim our relationship to place, there is hope for change.

We must acknowledge that people cannot sustain existence among slash piles.

We must relearn how to dance with the bones, not on them.